When I heard the following paper being presented at the 1988 Bahai Studies conference in New Zealand it seemed to me that the phrase by Abdul-Baha “the sun at high noon” meant when the timing is right or when time has passed.

Here is the whole text:

“The House of Justice, however, according to the explicit text of the Law of God, is confined to men; this for a wisdom of the Lord God’s, which will ere long be made manifest as clearly as the sun at high noon.”

Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Baha, Haifa: Baha’i World Centre, 1978, pp 79-80

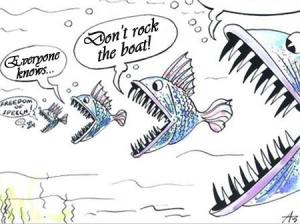

Over the years various Bahais have come up with all sorts of ‘reasons’ as to why women are not allowed to serve as members of the international body of the Bahai Administration (The Universal House of Justice) which fortunately can be easily dismissed as prejudice or ignorance because in most Bahai communities women are not treated with any lesser status than men. I am not suggesting that Bahai communities do not display aspects of sexism but in general I don’t see it being any worse than in the surrounding culture and as each day goes by, less Bahais insist that a women’s place is in the home raising children 🙂

So when someone would ask me about the inequality of not allowing women to serve on the Universal House of Justice (UHJ). I would throw up my hands and say I have no idea but I trust it will work out and that I am a Bahai and a feminist and Bahais do see the importance of gender equality. After hearing the paper, depending on the person’s interest I might add it seems to me to be a historical misunderstanding because Abdul-Baha’s 1902 text cited above refers to the all male membership of the Chicago House of Justice and not to the Universal House of Justice and a decade later Abdul-Baha changed this policy to allow women also to serve.

I now saw the context for this quotation from Abdul-Baha as wisdom because for the Persian man sent to oversee this first election at Abdul-Baha’s request, the idea that women could be members was too much of a strange idea. So “confined to men” meant in the 1902 Tablet, for a period of 10 years from the first tablet in 1902 to the change to allow women to be elected in 1912.

This paper also gives an overview on the development of the Bahai administration which began informally in Iran from about 1878 as well as some context for Baha’u’llah’s use of the word “rijal” which is the word used by Baha’u’llah for the members of a House of Justice.

Sen McGlinn wanted to publish this in a journal of essays, Soundings (see the essays that were published) but the UHJ would not allow this to be published. Then the authors were informed that they were not allowed to circulate this paper. Then in 2007 another letter of the UHJ said that they were unaware of any restrictions on the circulation of this paper. So this could go up on h-net.org where people now had access to this. Below this paper is a bit of discussion on this topic.

Here is the paper! It is also here on h-net.org but I am putting it here so there are two places it can be found. Please bear in mind that this was written in 1988 and so the statistics will be out of date. So far as I know no other Bahais have written on this topic since then. There have been a number of statements from the UHJ stating that the gender of the UHJ will never change.

The Service of Women on the Institutions of the Baha’i Faith

Presented in 1988 at the New Zealand Bahai Studies Association Conference, Christchurch.

Anthony A. Lee, Peggy Caton, Richard Hollinger, Marjan Nirou, Nader Saiedi, Shahin Carrigan, Jackson Armstong-Ingram, and Juan R. I. Cole

From 1844, the year of the founding of the Babi religion, to the present day, women have played important roles in Baha’i history. Babi and Baha’i women have often acted as leaders in the community, holding its highest positions and participating in its most important decisions. In the first days of His Revelation, the Bab Himself appointed Qurratu’l-‘Ayn, Tahirih, as one of His chief disciples – one of the nineteen Letters of the Living who were the first to believe in Him and were entrusted by Him with the mission of spreading His Faith and shepherding its believers. This remarkable woman would soon become one of the most radical and influential of the Bab’s disciples and the leader of the Babis of Karbala. Her vision and achievement have become legend. [1]

In later periods of Baha’i history, women have acted in central roles of leadership within the community. Bahiyyih Khanum, the Greatest Holy Leaf, the sister of ‘Abdu’l-Baha, several times in her lifetime was called upon to act as the de facto head of the Baha’i Faith. When ‘Abdu’l-Baha left the Holy Land to travel to the West, for example, He chose to leave the affairs of the Cause in the hands of His sister. Likewise, immediately after the ascension of ‘Abdu’l-Baha – before Shoghi Effendi, the new Guardian, could arrive in Palestine to assume control of the Faith, the Greatest Holy Leaf assumed leadership. The Baha’is in the Holy Land instinctively turned to her as their guide and protector. And again, during the Guardian’s absences from his duties during the early years of his ministry, he repeatedly entrusted the affairs of the Cause to the Greatest Holy Leaf. [2]

After the passing of Shoghi Effendi, women were once more called upon to serve the Baha’i Faith at its highest levels. The international leadership of the religion fell to the Hands of the Cause, the chief stewards of the Faith who had been appointed by the Guardian during his lifetime. The women Hands served along with the men to guide the Baha’i community through the turbulent years preceding the election of the Universal House of Justice. Once again, Baha’i women demonstrated their capacity to administer the affairs of the Faith at its highest levels.

The Baha’i Principle of Gradualism

Nonetheless, the service of women on the elected institutions of the Baha’i Faith has emerged only gradually. Although a few exceptional Baha’i women have always set the example for their sex, the role of women on Baha’i institutions in the community as a whole has not been comparable to that of men. Traditional notions of inequality, as well as the restrictions of a hostile environment, have caused the participation of women to lag behind.

Even to the present day, the participation of women on National Spiritual Assemblies, Boards of Counsellors, and Auxiliary Boards is not equal to that of men, as the charts show. A long road has yet to be travelled.

Participation of Women in Baha’i Institutions

“The equality of men and women is not, at the present time, universally applied.

In those areas where traditional inequality still hampers its progress we must take the lead in practicing this Baha’i principle. Baha’i women and girls must be encouraged to take part in the social, spiritual and administrative activities of their communities.”

The Universal House of Justice, Ridvan 1984.

The following table shows, by continent, the numbers of National Assemblies with the corresponding numbers of women members indicated by the column headings. For example, column 1, line 1, there are 4 Assemblies in Africa with no women members.

(Information provided by the Department of Statistics at the Baha’i World Centre, and reprinted from dialogue, volume 1, no. 3 (Summer/Fall 1986), p 31.)

The gradual emergence of women on the institutions of the Faith should not come as a surprise, however. Virtually all Baha’i laws and practices have gone through a gradual evolution in Baha’i history. The recognition of the principle of the equality of men and women, and its gradual application in the development of Baha’i Administration is no exception.

The principle of progressive revelation, the concept of the gradual emergence of divine purpose, is a universal principle which applies within the dispensation of each Manifestation, as well as between dispensations. Baha’u’llah Himself has explained:

Know of a certainty that in every Dispensation the light of Divine Revelation hath been vouchsafed to men in direct proportion to their spiritual capacity. Consider the sun. How feeble its rays the moment it appeareth above the horizon. How gradually its warmth and potency increase as it approacheth its zenith, enabling meanwhile all created things to adapt themselves to the growing intensity of its light. How steadily it declineth until it reacheth its setting point. Were it all of a sudden to manifest the energies latent within it, it would no doubt cause injury to all created things …

In like manner, if the Sun of Truth were suddenly to reveal, at the earliest stages of its manifestation, the full measure of the potencies which the providence of the Almighty hath bestowed upon it, the earth of human understanding would waste away and be consumed; for men’s hearts would neither sustain the intensity of its revelation, nor be able to mirror forth the radiance of its light. Dismayed and overpowered, they would cease to exist. [3]

The Universal House of Justice has demonstrated how this principle of progressive revelation has applied, and continues to apply, to the implementation of Baha’i law, particularly to the laws of the Kitab-i Aqdas. The Central Figures of the Faith have promulgated these laws only gradually as the condition of the Baha’i community would allow. [4]

Similarly, ‘Abdu’l-Baha recognised that women could not take their rightful place in the affairs of the world all at once. Throughout history women have been deprived of education and opportunity. Therefore, it was impossible that they would be able to immediately play an equal role in Baha’i life. But ‘Abdu’l-Baha has insisted that all distinctions of sex will be erased once women attain proper education and experience. He says:

Woman’s lack of progress and proficiency has been due to her need for equal education and opportunity. Had she been allowed this equality, there is no doubt she would be the counterpart of man in ability and capacity. [5]

In a talk given in New York, ‘Abdu’l-Baha again pinpoints education as the key to women’s equality:

…if woman be fully educated and granted her rights, she will attain the capacity for wonderful accomplishments and prove herself the equal of man. She is the coadjutor of man; his complement and helpmeet. Both are human, both are endowed with potentialities of intelligence and embody the virtues of humanity. In all human powers and functions they are partners and co-equals. At present in spheres of human activity woman does not manifest her natal prerogatives owing to lack of education and opportunity. [6]

In Paris He said:

…the female sex is treated as though inferior, and is not allowed equal rights and privileges. This condition is not due to nature, but to education. In the Divine Creation there is no such distinction. Neither sex is superior to the other in the sight of God. Why then should one sex assert the inferiority of the other…If women received the same educational advantages as those of men, the result would demonstrate the equality of capacity of both for scholarship. [7]

On another occasion he made the same point:

The only difference between them [ie: men and women] now is due to lack of education and training. If woman is given equal opportunity of education, distinction and estimate of inferiority will disappear. [8]

And again:

Therefore, woman must receive the same education as man and all inequality be adjusted. Thus, imbued with the same virtues as man, rising through all the degrees of human attainment, women will become the peers of men, and until this equality is established, true progress and attainment for the human race will not be facilitated. [9]

It was clearly ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s position that lack of education and opportunity had relegated woman to an inferior position in society, and that through education and experience all inequalities of sex would be gradually removed. His own policies and actions concerning the service of women on the institutions of the Faith reflected this belief in gradualism.

The First Baha’i Institutions

Any investigation of the history of the development of the Baha’i Administrative Order will reveal that Baha’i women only gradually took their place beside the men in this area of service – and not without struggle. This has been especially true in the East, where women were most heavily restricted. But lack of education and other cultural circumstances have affected the participation of women on Baha’i institutions all over the world.

The first Hands of the Cause appointed by Baha’u’llah were, for example, all males. ‘Abdu’l-Baha appointed no additional Hands, and it was only during the ministry of Shoghi Effendi that women were appointed to this rank. Even so, it has been only Western Baha’i women who have been found qualified for this distinction.

At later times, when the first Auxiliary Boards to the Hands of the Cause were appointed, and then the first contingents of Boards of Counsellors, women were included. But circumstances dictated that it be mostly Western women who were appointed, and that their numbers were far fewer than those of men. As the above chart shows, that situation remains the same today. This is not due to any policy of discrimination on the part of the institutions of the Faith, but simply due to historical circumstances. As the position of women improves – especially in Asia and Africa – with respect to education and experience, we can expect that the current situation will change in favour of more participation of women.

The House of Justice of Tehran

The struggle for the equal participation of women in Baha’i Administration has been played out most dramatically, however, in the arena of the development of local institutions. The first of these bodies was formed in Tehran, Iran, at the initiative of individual believers.

In 1873, Baha’u’llah revealed the Kitab-i-Aqdas, the Most Holy Book, His book of laws. Here He established the institution of the House of Justice (bayt al-‘adl). The Kitab-i-Aqdas states:

The Lord hath ordained that in every city a House of Justice (bayt al-‘adl) be established wherein shall gather counsellors to the number of Baha [i.e., nine], and should it exceed this number it does not matter … It behoveth them to be the trusted ones of the Merciful among men and to regard themselves as the guardians appointed of God for all that dwell on earth. It is incumbent on them to take counsel together and to have regard for the interests of the servants of God, for His sake, even as they regard their own interests, and to choose that which is meet and seemly. [10]

In the same book it is written:

O ye Men of Justice! (rijal al-‘adl) Be ye in the realm of God shepherds unto His sheep and guard them from the ravening wolves that have appeared in disguise, even as ye would guard your own sons. Thus exhorteth you the Counsellor, the Faithful. [11]

There are other references in the Kitab-i-Aqdas to the House of Justice (bayt al-‘adl) or the Place of Justice (maqarr al-‘adl) which define its function and fix some of its revenues. In most cases, these references are not specific but refer to the general concept of a House of Justice rather than a particular institution. The Universal House of Justice has explained:

In the Kitab-i-Aqdas Baha’u’llah ordains both the Universal House of Justice and the Local Houses of Justice. In many of His laws He refers simply to “the House of Justice” leaving open for later decision which level or levels of the whole institution each law would apply to. [12]

Although the Kitab-i-Aqdas was revealed in ‘Akka in 1873, it was withheld for some time by Baha’u’llah before it was distributed to the Baha’is of Iran. [13]

It appears that it was not until 1878 that the Baha’is of Tehran received copies of the book and began to implement some of its laws in their personal lives. Upon reading the Kitab-i Aqdas, Mirza Asadu’llah Isfahani, a prominent Baha’i teacher living in Tehran, was particularly struck by the command of Baha’u’llah that a House of Justice should be established by the Baha’is in every city.

Mirza Asadu’llah is an important figure in Baha’i history: he eventually married the sister of ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s wife; he was (as we shall see) one of the earliest Baha’i teachers sent to America by ‘Abdu’l-Baha to instruct the new Western believers and he later accompanied ‘Abdu’l-Baha on his travels in Europe. In any case, in 1878 he was the first to undertake the organization of a local House of Justice in Iran. He took the initiative to invite eight other prominent believers to form a body, responding to the laws of the Kitab-i Aqdas, which they referred to as bayt al-‘adl (House of Justice) or bayt al-a’zam (the Most Great House).

The organization of this first House of Justice was kept a secret, even from the believers. However, it met sporadically in the home of Mirza Asadu’llah for a couple of years. After consulting with this body, the prominent Baha’i men who had been invited to attend its meetings would seek to take action as individual Baha’i teachers that would implement its decisions.

Around 1881, the Tehran House of Justice was reorganized and more members were added. The House adopted a written constitution and pursued its activities with more organization and vigour than before. The constitution mandated, however, that the meetings remain strictly confidential, hidden from the body of the believers.

This constitution also assumes that the members of the House would all be men (aqayan). Naturally, considering the social conditions in Iran at the time, no other arrangement was possible.

Some of the minutes of this early House of Justice survive today. It was a gathering of the older and more prominent Baha’i men of Tehran. Meetings were attended by invitation only, and at times included fourteen members or more. Eventually, this meeting came to be called the Consultative Gathering (majlis-i shur), while the house where the body met was referred to as the House of Justice (bayt al-‘adl).

These meetings sought to assist and protect the Baha’is through consultation on various problems. The House in Tehran sent Baha’i teachers to other cities in Iran to organize Houses of Justice there. Again, the decisions of the House were always carried out by individuals, and the consultations remained secret.

The organization of this body eventually met with some controversy. One important Baha’i teacher, Jamal-i Burujurdi, who later – in the time of ‘Abdu’l-Baha – would become a notorious Covenant-breaker, objected strongly to the organization of a House of Justice in Tehran. Because of these objections, the Baha’is involved on the House appealed to Baha’u’llah for guidance. Baha’u’llah replied with a Tablet in which He approved of the House of Justice and strongly upheld the principle of consultation in the Baha’i Faith. [14]

Early Organisation in America

When the first rudimentary local Baha’i institutions were organized in the United States, their membership was also confined to men. Later, as various forms of Baha’i organization at the local level became more common, men and women served together. But it was the understanding of the Baha’is at the turn of the century that consultative bodies in the Baha’i community should be composed of men. This understanding became firmly institutionalized in the largest Baha’i communities of New York, Chicago, and Kenosha, Wisconsin, and was sanctioned by ‘Abdu’l-Baha.

A scholarly history of the beginnings of Baha’i organization in America has yet to be written. Many of the details of these events have yet to be uncovered. However, it appears that the early American Baha’is were moved to form local councils for the first time in 1900, as a consequence of the defection of Ibrahim Kheiralla from the community. Kheiralla, a Lebanese Christian who had been converted to the Baha’i Faith in Egypt by a Persian Baha’i, ‘Abdu’l-Karim Tihrani, had brought the Baha’i teachings to America and had acted as the head of the Faith in the West until that point. His repudiation of ‘Abdu’l-Baha as the rightful leader of the Faith and chosen successor to his Father caused a temporary rift among the Baha’is.

In the fall of 1899, Edward Getsinger, a leading American Baha’i, appointed five men as a “Board of Counsel” for the Baha’is of northern New Jersey. [15] Isabella Brittingham was made the honorary corresponding secretary, but was not a member of the body. Later, in a letter dated March 21, 1900, Thornton Chase wrote from Chicago:

“We have formed a ‘Board of Council’ with 10 members.”

In this letter, Chase lists the names of nine of these members, all of whom were men. [16]

In June of 1900, however, it appears that the Chicago Board was reorganized. ‘Abdu’l-Karim Tihrani had travelled to America at the request of ‘Abdu’l-Baha and had arrived in Chicago at the end of May. The Baha’is of Chicago immediately asked him to draw up rules and regulations that would govern the affairs of their Board. [17] As a result, the Board of Counsel was expanded to nineteen members, some of whom were women. In a statement to the press the Baha’is indicated that this Board was being organized to replace Ibrahim Kheiralla, whom they repudiated as the leader of the Faith. [18]

Although ‘Abdu’l-Karim remained in Chicago for only a short time, his nineteen-member Board appears to have functioned for about a year. However, on May 15, 1901, a nine-member, all-male House of Justice was elected in Chicago to replace it. This was done at the direction of Mirza Asadu’llah Isfahani, who had been sent to America by ‘Abdu’l-Baha. Writing to the House of Justice in New York that had already been established, the Chicago House wrote:

Recently His Honor, Mirza Assad’Ullah, received a Tablet from the Master, Abdul-Baha, in which He has positively declared to be necessary the establishment here of the House of Justice by election by the believers with order and just dealing. According to this blessed Announcement, our believers have elected those whom they deemed best fitted, and thus The House of Justice was established. [19]

It was Mirza Asadu’llah who instructed the Baha’is of Chicago that the new House of Justice should be composed only of men. He and his company appear to have regarded the nineteen-member Board as illegitimate, possibly because women served as members.

The change to an all-male institution was not accomplished without anguish. Writing years later, Fannie Lesch, who had served on the Board of Counsel, wrote:

We had a Council Board of men and women after Dr. Kheiralla left us…

Mirza Assad’Ullah ignored us, although they were all invited to meet with us, and he established a House of Justice of men only… [20]

Only days after the election of the Chicago House of Justice, a Ladies’ Auxilliary Board was organized at the suggestion of Mrs. Ella Nash and Mrs. Corinne True. This Board was later to be known as the Women’s Assembly of Teaching. It appears that the Ladies’ Auxilliary was able to maintain control of the funds of the Chicago Baha’i community despite the election of the House of Justice. [21]

Men of Justice

The belief that women were not eligible for service on local Baha’i institutions was based on the language of certain passages of the Kitab-i Aqdas which refer to the House of Justice. Of course, as we have noted above, these passages do not make a distinction between local, national, and international bodies. The institution as a whole is addressed. Baha’u’llah twice uses the Arabic word rijal (gentlemen) to refer to the members of the Houses of Justice. He says:

O ye Men (rijal) of Justice! Be ye in the realm of God shepherds unto His sheep… [22]

And:

We have designated a third of all fines for the Place of Justice (maqarr al-‘adl), and exhort its members (rijal) to show forth perfect equity… [23]

The word rijal (plural; singular is rajul) is exclusively masculine in Arabic. A dictionary would render an English definition of rajul as: man, gentleman; important man, statesman, nobleman. (A related form of the word, rujula or rujuliyya, would be translated as: masculinity; virility.) Since Baha’u’llah addressed the members of the Houses of Justice using this term, it appears that it was universally assumed that only men were eligible for service on such institutions.

The word rijal, meaning men, is used in the Qur’an and is part of an important passage which establishes the relationship between men and women in Islam (Qur’an 4:34):

Men (rijal) are superior to women (nisa’) on account of the qualities with which God hath gifted the one above the other, and on account of the outlay they make from their substance for them.

However, Baha’u’llah has in His Writings clearly established the principle of the equality of men and women. It is therefore possible that when He used the word rijal He did not intend its normal meaning.

Although rijal is the normal Arabic word for men (as opposed to women), there are passages in the Writings of Baha’u’llah that indicate that He may have used the term in a special sense. Such passages suggest that, in a Baha’i context, the word may be understood to include women. Baha’u’llah has stated that women in His Cause are all to be accorded the same station as men – and He has used the very term rijal to make this point. For example, He writes:

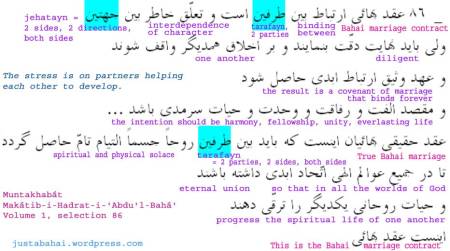

Today the Baha’i women (lit., the leaves of the Holy Tree) must guide the handmaidens of the earth to the Lofty Horizon with the utmost purity and sanctity. Today the handmaidens of God are regarded as gentlemen (rijal). Blessed are they! Blessed are they! [24]

And in another passage:

Today whoever among the handmaidens attains the knowledge of the Desire of the World [i.e., Baha’u’llah] is considered a gentleman (rajul) in the Divine Book. [25]

And in another place:

…many a man (rajul) hath waited expectant for God’s Revelation, and yet when the Light shone forth from the horizon of the world, all but a few turned their faces away from it. Whosoever from amongst the handmaidens hath recognized the Lord of all Names is recorded in the Book as one of those men (rijal) by the Pen of the Most High. [26]

Likewise, ‘Abdu’l-Baha in one of his Tablets has made the same point:

Verily, according to Baha’u’llah, women are judged as gentlemen (rijal). [27]

However, such passages were not raised as an issue at the time, either because the believers were not aware of them, or because they did not find them applicable. Certainly, the American Baha’is had no access to these texts and had to rely on the understandings of the Persian teachers who were sent by ‘Abdu’l-Baha to guide them.

Names and Terminology

In any case, it was the goal of Mirza Asadu’llah to establish a House of Justice among the believers in Chicago, as he indicated to the Baha’is that ‘Abdu’l-Baha had instructed him to do. He had been at the centre of the organization of the first House of Justice in Tehran, and he assumed a similar role in Chicago. At his direction, the Baha’is in Chicago elected nine men by ballot to a new institution. Those elected were: George Lesch, Charles H. Greenleaf, John A. Guilford, Dr. Rufus H. Bartlett, Thornton Chase, Charles Hessler, Arthur S. Agnew, Byron S. Lane and Henry L. Goodall. [28]

At its first meeting, the House of Justice decided to raise the number of its members to twelve. The body appointed three additional Baha’i men to serve. The minutes of the meeting read:

Motion made and seconded that Messrs. Ioas, Pursels and Doney be selected as add’n [additional] members of this Board of Council. Said motion approved by Board. Secretary instructed to notify said members. [29]

This action was taken, no doubt, in accordance with the statement of Baha’u’llah in the Kitab-i Aqdas that the minimum number of members for a House of Justice is nine, “and should it exceed this number it does not matter.” [30]

It is instructive to note that, in its first minutes, the secretary of the House of Justice refers to it as a “Board of Council.” This illustrates the fluidity of terminology that was used for Baha’i meetings and institutions at the time.

Standard terms for the Baha’i institutions did not become fixed and universal until well after the passing of ‘Abdu’l-Baha. Today, the elected local and national Baha’i institutions are known as “Spiritual Assemblies,” while the term “House of Justice” is reserved exclusively for the supreme, international institution. In the early years of this century, however, though these same terms were in use among the Baha’is, they were not used in the same ways. ‘Abdu’l-Baha himself confirmed the legitimacy of the election of the first Chicago House of Justice. A Tablet, probably received in September 1901, is addressed from ‘Abdu’l-Baha “To the members of the House of Justice, the servants of the Covenant, the faithful worshippers of the Holy Threshold of the Beauty of El-Abha.”

Two such Tablets addressed to the House of Justice of Chicago are translated in the compilation

Tablets of Abdul-Baha Abbas. [31]

Shoghi Effendi, writing much later in 1929, has discussed the significance of these Tablets. He says:

That the Spiritual Assemblies of today will be replaced in time by Houses of Justice, and are to all intents and purposes identical and not separate bodies, is abundantly confirmed by ‘Abdu’l-Baha Himself. He has in fact in a Tablet addressed to the members of the first Chicago Spiritual Assembly, the first elected Baha’i body instituted in the United States, referred to them as members of the “House of Justice” for that city, and has thus with His own pen established beyond any doubt the identity of the present Baha’i Spiritual Assemblies with the House of Justice referred to by Baha’u’llah. For reasons which are not difficult to discover, it has been found advisable to bestow upon the elected representatives of Baha’i communities throughout the world the temporary appellation of Spiritual Assemblies, a term which, as the position and aims of the Baha’i Faith are better understood and more fully recognised, will gradually be superseded by the permanent and more appropriate designation of House of Justice. [32]

This “temporary appellation” was assumed at the instruction of ‘Abdu’l-Baha about a year after the election of the Chicago House of Justice. The minutes of the House of Justice for May 10, 1902, read:

Mr/ Greenleaf stated that he was instructed by Mirza Assad Ullah to inform this Body that here after and until otherwise informed it shall be known as the “House of Spirituality,” in accordance with a Tablet recently received from our Master.

Motion made and seconded that the command of Master changing name of this Body as transmitted by Mirza Assad Ullah be entered upon our records.

Approved by House.

Motion made and seconded that a copy (translation) of that portion of tablet setting forth the change as above mentioned be procured and placed on file.

Approved by House. [33]

Extracts from this Tablet were indeed translated for the House of Justice, now the House of Spirituality. The heading to the translation indicates that the Tablet was received in Chicago by Mirza Assadu’llah on May 3, 1902. One extract reads:

The House of Justice of Chicago should be called “the House of Spirituality” (or the Spiritual House).

In short, no one must hurt the weak ones, there, but must treat them in kindness. Because now is the cycle of kindness and forgiveness to all people. [34]

In what is apparently a second Tablet on the subject, ‘Abdu’l-Baha explained the reasons for the change. This Tablet was, some time later, translated and published:

The signature of that meeting should be the Spiritual Gathering (House of Spirituality) and the wisdom therein is that hereafter the government should not infer from the term “House of Justice” that a court is signified, that it is connected with political affairs, or that at any time it will interfere with governmental affairs. Hereafter, enemies will be many. They would use this subject as a cause for disturbing the mind of the government and confusing the thoughts of the public. The intention was to make known that by the term Spiritual Gathering (House of Spirituality), that Gathering has not the least connection with material matters, and that its whole aim and consultation is confined to matters connected with spiritual affairs. This was also instructed (performed) in all Persia. [35]

At the same time, and in the original Tablet received on May 3, ‘Abdu’l-Baha had instructed that the name of the Women’s Assembly of Teaching be changed to the “Spiritual Assembly.” He instructed that “Spiritual Assemblies” should be organized in every place.

However, although the change of name for the House of Justice was effected immediately, the instruction to change the name of the women’s institution was ignored. This is probably because the translation of this command into English was so poor as to render it incomprehensible. [36]

And so we read the following in the minutes of the House of Spirituality three years later (July 29, 1905):

Mr. Windust read portions of the Tablet received from the Master in May, 1902 authorizing change of name of this body from “House of Justice” to “House of Spirituality”; as it also stated in said Tablet that the name of the Women’s “Assembly of Teaching” be changed to “Spiritual Assembly.” It was decided that this matter be spoken of at some future joint meeting [with the women’s group], as it had evidently been overlooked. [37]

As we have seen in the Tablets quoted above, in the first year after the election of the Chicago House of Justice, ‘Abdu’l-Baha Himself used various terms to refer to that body. (Of course, we have quoted His Tablets in translation – the translations available to the Baha’is at the time.) These Tablets reflect the use of at least three different designations during this period: House of Justice (bayt al-‘adl) in the earliest Tablets, House of Spirituality (probably, bayt-i rawhani) in one Tablet, and Spiritual Gathering (mahfil-i rawhani) in another.

This last term, mahfil-i rawhani, can also be translated as “Spiritual Assembly.” However, it was usually translated as “House of Spirituality” in the publications and translations made at this time, even though this translation was in error. The Chicago body came to be known as the House of Spirituality from 1902, and so the translators rendered ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s references to it in these words, even if the original Persian did not warrant such a designation. This was because the term “Spiritual Assembly” had no fixed meaning in the early community and could refer to a number of different Baha’i meetings.

‘Abdu’l-Baha had asked, for example, that the term be used for the Ladies’ Auxiliary. It was also used by the Baha’is of this time to refer to any Baha’i community as a whole, some weekly teaching meetings, any consultative body, or any gathering of believers.

Terms used to designate the local administrative body were also fluid in ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s writings. In addition to the three designations above, the following additional names can be found: mahfil-i shur (Assembly of Consultation), mahfil-i shur rawhani (Spiritual Assembly of Consultation), bayt al-‘adl rawhani (Spiritual House of Justice), anjuman (Council), anjuman-i adl (Council of Justice), and marakiz-i ‘adl (Centres of Justice). [38]

The Women’s Struggle

The election of an all-male House of Justice in Chicago was a development to which some of the women in the Baha’i community were never reconciled. It is Corinne True in particular who stands out in the struggle to overturn the exclusion of women from that body. After the election, she immediately helped to organize the Women’s Assembly of Teaching which worked side by side with the House – and not always harmoniously – for over a decade. Beyond this, she appealed directly to ‘Abdu’l-Baha, asking that women be elected to the House of Justice.

Mrs. True’s letter, which has recently come to light, indicates clearly that the change to an all-male body was the cause of some dispute. She writes to ‘Abdu’l-Baha:

There has existed a difference of opinion in our Assembly [that is, the Chicago community] as to how it should be governed. Every believer desires to carry out the Commands of the Blessed Perfection [Baha’u’llah] but we want to know from our Lord himself [that is, ‘Abdu’l-Baha] what these Commands are, as they are written in Arabic and we do not know Arabic. Will Our Lord write me direct from Acca and not have it go through any Interpretor [sic] in America and thus grant me the Authority to say the Master says thus & so, for he has written it to me…

Many in our Assembly feel that the Governing Board in Chicago should be a mixed Board of both men & women. Woman in America stands so conspicuously for all that is highest & best in every department and for that reason it is contended the affairs should be in the hands of both sexes. [39]

She was, however, disappointed when the Master would not support her point of view. He confirmed the practice of electing only males to the Baha’i governing board of Chicago, admonishing her to be patient. She appears to have received her reply from ‘Abdu’l-Baha in June of 1902, but refrained from sharing this Tablet with the Chicago House until the fall of that year.

The Tablet is a famous one and reads in part (in modern translation):

Know thou, O handmaid, that in the sight of Baha, women are accounted the same as men, and God hath created all humankind in His own image, and after His own likeness. That is, men and women alike are the revealers of His names and attributes, and from the spiritual viewpoint there is no difference between them. Whosoever draweth nearer to God, that one is the most favoured, whether man or woman. How many a handmaid, ardent and devoted, hath, within the sheltering shade of Baha, proved superior to the men, and surpassed the famous of the earth.

The House of Justice, however, according to the explicit text of the Law of God, is confined to men; this for a wisdom of the Lord God’s, which will ere long be made manifest as clearly as the sun at high noon.

As to you, O ye other handmaids who are enamoured of the heavenly fragrances, arrange ye holy gatherings, and found ye Spiritual Assemblies, for these are the basis for spreading the sweet savours of God, exalting His Word, uplifting the lamp of His grace, promulgating His religion and promoting His Teachings, and what bounty is there greater than this? [40]

Since ‘Abdu’l-Baha had confirmed that women should be excluded from the Chicago House of Justice (later, House of Spirituality), this practice continued for some time, in Chicago and elsewhere. We might assume that the belief that women were to be permanently excluded from local Baha’i executive bodies was widespread, at least amongst the men. Women were to be involved in forming women’s groups, which ‘Abdu’l-Baha had named “Spiritual Assemblies” in one Tablet.

That did not end the issue, of course. It appears that American Baha’i women continued to discuss the possibility of membership on governing boards, with Corinne True being prominent among them. In 1909, Mrs. True received a Tablet from ‘Abdu’l-Baha in response to her insistent questioning. It reads, in part:

According to the ordinances of the Faith of God, women are the equals of men in all rights save only that of membership on the Universal House of Justice [bayt al-‘adl ‘umumi], for, as hath been stated in the text of the Book, both the head and the members of the House of Justice are men. However, in all other bodies, such as the Temple Construction Committee, the Teaching Committee, the Spiritual Assembly, and in charitable and scientific associations, women share equally in all rights with men. [41]

This new Tablet from ‘Abdu’l-Baha to Corinne True appears to have opened up a nationwide controversy over the rights of women to serve on Baha’i institutions. The use of the term “Universal House of Justice” in this Tablet caused some confusion. Corinne True and others assumed that ‘Abdu’l-Baha intended by this Tablet that women were now to be admitted to membership on local Baha’i bodies, and more particularly to membership on the Chicago House of Spirituality.

Thornton Chase related the controversy which erupted in Chicago in a letter written a few months later (January 19, 1910):

Several years ago, soon after the forming of the “House of Justice” (name afterward changed by Abdul-Baha to House of Spirituality on account of political reasons – as stated by Him – and because also of certain jealousies) Mrs. True wrote to Abdul-Baha and asked if women should not be members of that House. He replied distinctly, that the House should be composed of men only, and told her that there was a wisdom in this. It was a difficult command for her to accept, and ever since (confidentially) there has been in that quarter and in those influenced by her a feeling of antagonism to the House of Spirituality, which has manifested itself in various forms …

… Mrs True received a Tablet, in which it was stated (in reply to her solicitation) that it was right for women to be members of all “Spiritual Gatherings” except the “Universal House of Justice”, and she at once construed this to mean, that women were to be members of the House of Spirituality and the Council Boards, because in some of the Tablets for the House, it had been addressed as the “Spiritual Assembly” or “Spiritual Gathering”. But the House of Spirituality could not so interpret the Master’s meaning… [42]

The difference of opinion was deep and serious. It took place within a wider context of gender tensions within the American Baha’i community at the time. The Chicago House of Spirituality consulted on the new Tablet to Corinne True at its meetings on August 31, 1909, and September 7, 1909. While it seemed clear to them that the Tablet did not admit women to membership on the House of Spirituality, they decided to write to ‘Abdu’l-Baha for a clarification of His meaning. [43]

It appears that no record of a reply to the House on this point has survived. But, in the event, the practice of excluding women from membership did not change. The men of Chicago assumed that ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s reference to the “Universal House of Justice” intended the local Chicago institution. This is a reasonable assumption, given the lack of fixed terminology at the time.

The word ‘umumi, with which ‘Abdu’l-Baha qualified His reference to the House of Justice in Arabic, means public, general, or universal. Since it was known that Corinne True had asked about women’s service on the Chicago House – which was understood to be a House of Justice, even if designated a House of Spirituality for various reasons – His reply seemed to indicate that only men could serve on the general (or universal) body, while women could serve on all subordinate bodies, such as the Assembly of Teaching, the Philanthropic Association, and so forth. And this is the interpretation of the Tablet that would stand for some years to come.

In May of 1910, Thornton Chase wrote to a believer about this question, which was still being debated:

As to women being members of the House, there is no question at all. ‘Abdul-Baha’s reply to Mrs True years ago, settled that, viz, that the members of the House should be men, and that the time would come when she would see the wisdom of that. This was in direct answer to her question to Him as to this matter. He has never changed that command, and He cannot, because it is the command of Baha’o’llah also, as applied to such bodies of business controllers.

But, in a Tablet to me, ‘Abdu’l-Baha said “The House of Spirituality must encourage the women as much as possible”. There is the whole procedure. “Encourage the women as much as possible”. That is what He does: that is what we should do. Not to be members of the H. of S., but to all good works in the Cause, which they can possibly accomplish. It seems to me that the matter of membership in H. of S. should be simply ignored, not talked about, but if it obtrudes itself too strongly, just get out that Tablet to Mrs. True and the one to me (just mentioned) and offer them as the full and sufficient answer. [44]

Chase’s views are undoubtedly representative of the understandings of the majority of Baha’is at the time. It was the common understanding that the Chicago House of Spirituality was properly composed of men only, and that ultimately all local Baha’i boards should be similarly composed. This was a position which was repeatedly sustained by ‘Abdu’l-Baha, but which was never fully accepted by some Baha’i women.

In Kenosha, which had had an all-male “Board of Consultation” for some years, the issue of women’s service on the Board became a matter of dispute in 1910, as a result of Corinne True’s 1909 “Universal House of Justice” Tablet. On July 4, 1910, the Kenosha Board wrote to the House of Spirituality in Chicago asking if they had any Tablets from ‘Abdu’l-Baha which instructed that women should be elected to local institutions. They explained that two of the Baha’i ladies in their community had insisted that such Tablets existed. [45]

The reply from the House of Spirituality, dated July 23, 1910, is very instructive. [46] The House was able to find three Tablets from ‘Abdu’l-Baha which had bearing on the subject. One was the 1909 Tablet to Corinne True which had opened the controversy. Two others had been received from ‘Abdu’l-Baha in 1910, in reply to more inquiries.

In a Tablet to Louise Waite (April 20, 1910), ‘Abdu’l-Baha had instructed:

The Spiritual Assemblies which are organized for the sake of teaching the Truth, whether assemblies for men, assemblies for women or mixed assemblies, are all accepted and are conducive to the spreading of the Fragrances of God. This is essential. [47]

‘Abdu’l-Baha goes on to state that the time had not come for the establishment of the House of Justice, and he exhorts the men and the women to produce harmony and conduct their affairs in unity.[48]

In another Tablet directed to the Baha’is of Cincinnati, where the question of women’s participation in local organization had also become an issue, ‘Abdu’l-Baha wrote something similar:

It is impossible to organize the House of Justice in these days; it will be formed after the establishment of the Cause of God. Now the Spiritual Assemblies are organized in most of the cities, you must also organize a Spiritual Assembly in Cincinnati. It is permissible to elect the members of the Spiritual Assembly from among the men and women; nay, rather, it is better, so that perfect union may result. [49]

The House of Spirituality concluded from these Tablets that:

…in organizing Spiritual Assemblies of Consultation now, it is deemed advisable by Abdul-Baha to have them composed of both men and women. The wisdom of this will become evident in due time, no doubt. [50]

By this time, Baha’is in different parts of the United States had established a variety of boards and committees as a means of local organization. Women had served on the Washington, D.C., “Working Committee” since its formation in 1907. They had been a part of the Boston “Executive Committee” from its beginning in 1908. Women also acted as officers of communities in places where Baha’is had elected no corporate body. But these were regarded, for the most part, as temporary, ad-hoc organizations not official Baha’i institutions, which were thought to be properly all male.

‘Abdu’l-Baha’s Tablets recognized all of these local bodies as “Spiritual Assemblies” (or Spiritual Gatherings, mahfil-i rawhani) and by 1910, He was urging that these Assemblies consist of both men and women. The House of Spirituality in Chicago was obviously puzzled by this command, though it expressed confidence that the wisdom of mixed Assemblies would “become evident in due time.”

However, since it knew that the Kenosha Board of Consultation had been established as an all-male body in accordance with earlier instructions from ‘Abdu’l-Baha, the House of Spirituality suggested that the Kenosha Baha’is might wish to take a vote to determine whether a majority of believers would be in favour of a change. [51]

Rather than do this, however, the Kenosha Board of Consultation submitted the question to ‘Abdu’l-Baha. The “supplication” (as they termed it) was signed by all of the men of the Board. It asked if the Board should be dissolved, to be reelected with women as members. The Board members pledged to the Master that if it was His wish they would dissolve, but they stated that their intentions had been pure at the founding of the Board and that it had been established in accordance with a Tablet that had been revealed for the House of Spirituality some years before. [52]

‘Abdu’l-Baha, however, would not support the idea of dissolving the all-male Board.

His reply, received March 4, 1911, explains:

Now Spiritual Assemblies must be organized and that is for teaching the Cause of God. In that city you have a spiritual Assembly of men and you can establish a spiritual Assembly for women. Both Assemblies must be engaged in diffusing the fragrances of God and be occupied with the service of the Kingdom. The above is the best solution for this problem … [53]

As in other Tablets, He stated that conditions for the establishment of the House of Justice did not yet exist, and He urged unity between the men and women of the Baha’i community. And so, through 1911, the status quo that had been established by Mirza Assadu’llah in Chicago in 1901, with the election of the first American House of Justice, held firm.

All-male institutions continued to function in the most important Baha’i communities. These were supplemented by parallel women’s groups. A variety of committees and boards had been established in smaller Baha’i communities that included women as members, but these were regarded by most Baha’is as only informal groups. While ‘Abdu’l-Baha was urging that new “Spiritual Assemblies” include both men and women, He would not sanction the reorganization of the longer-established male bodies. Baha’i women in various parts of the country continued to discuss the need for change.

The Change Comes

It was not until 1912, during the visit of ‘Abdu’l-Baha to America, that a decisive change was finally made. While ‘Abdu’l-Baha was in New York, He sent word to the Baha’is of Chicago that the House of Spirituality should be reorganized and a new election held. He chose Howard MacNutt, a prominent Baha’i from Brooklyn, to travel to Chicago as His personal representative. MacNutt was instructed to hold a new election for a “Spiritual Meeting” (probably mahfil-i rawhani) of the Baha’is of Chicago. For the first time, women were eligible for election to this body.

MacNutt arrived in Chicago on August 8, 1912. At ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s instructions, a feast was held on August 10, at the home of Mr. and Mrs. George Lesch, where the entire Chicago Baha’i community was invited to be the guests of ‘Abdu’l-Baha. MacNutt delivered to the community ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s message of unity and love. The election was held the following day on August 11.

The Baha’i magazine, Star of the West, carried this account of that historic election:

On Sunday evening, the 11th, the Chicago Assembly [meaning here, the whole Baha’i community] selected a “Spiritual Meeting” of nine, composed of men and women, whose service – according to the wish of Abdul-Baha – is, first, to promulgate the teachings of the Revelation, and, second, to attend to other matters necessary to the welfare of the assembly. Mr. MacNutt was present and gave an inspiring address. [54]

A long struggle had ended.

Baha’i Institutions in the East

From the time of the dissolution of the Chicago House of Spirituality and its reelection, service on local Baha’i institutions has always remained open to women in America. ‘Abdu’l-Baha had made it perfectly clear that the restrictions placed on women in this regard were intended to be only temporary ones. From that point forward, women were fully integrated into the emerging Baha’i Administration erected in the West.

The same was not true in the East, however. In Iran and in the rest of the Muslim world, social conditions made it impossible for the restriction on women’s participation on local institutions to be lifted for some time. Local and National Spiritual Assemblies in Iran were limited to male membership during the entire period of the ministry of ‘Abdu’l-Baha, and for most of the ministry of Shoghi Effendi. Again, the principle of gradualism was at play.

Of course, there were Baha’i women in Iran, as well in the United States, who campaigned for a greater role for women in the Baha’i community. Their concerns were not only with participation on local Houses of Justice, but also with the elimination of other social restrictions, such as the use of the veil in public. In a Tablet to one such woman activist, ‘Abdu’l-Baha urged restraint and recommended a gradual approach:

The establishment of a women’s assemblage (mahfil) for the promotion of knowledge is entirely acceptable, but discussions must be confined to educational matters. It should be done in such a way that differences will, day by day, be entirely wiped out, not that, God forbid, it will end in argumentation between man and women. As in the question of the veil, nothing should be done contrary to wisdom. …

Now the world of women should be a spiritual world, not a political one, so that it will be radiant. The women of other nations are all immersed in political matters. Of what benefit is this, and what fruit doth it yield? To the extent that ye can, ye should busy yourself with spiritual matters which will be conducive to the exaltation of the Word of God and of the diffusion of His fragrances. Your demeanour should lead to harmony amongst all and to coalescence and the good-pleasure of all…

I am endeavouring, with Baha’u’llah’s confirmations and assistance, so to improve the world of the handmaidens [that is, the world of women] that all will be astonished. This progress is intended to be in spirituality, in virtues, in human perfections and in divine knowledge. In America, the cradle of women’s liberation, women are still debarred from political institutions because they squabble. (Also, the Blessed Beauty has said, “O ye Men [rijal] of the House of Justice.”) Ye need to be calm and composed, so that the work will proceed with wisdom, otherwise there will be such chaos that ye will leave everything and run away. “This newly born babe is traversing in one night the path that needeth a hundred years to tread.” In brief, ye should now engage in matters of pure spirituality and not contend with men. ‘Abdu’l-Baha will tactfully take appropriate steps. Be assured. In the end thou wilt thyself exclaim, “This was indeed supreme wisdom!” [55]

Baha’i women were not admitted to service on the institutions of the Faith in Iran until 1954. But this restriction was understood to be temporary, to be removed as soon as circumstances would permit. As Iranian society allowed a greater role for women in general, and as Baha’i women became more educated and more prepared for administrative service, this restriction was lifted. The Guardian eventually made women’s participation on Baha’i institutions in the East one of the goals of the Ten Year World Crusade (1953-1963). His hopes were rewarded by the signal distinction which some Baha’i women have achieved as administrators on local Assemblies and on the National Assembly of Iran.

The International House of Justice

The only remaining body within the Baha’i Faith whose membership continues to be limited to men is its supreme institution, the Universal House of Justice. First established in 1963, the Universal House of Justice is elected by the members of the National Spiritual Assemblies of the world. Naturally, the electors include many women. But the members of the House of Justice itself, from its inception, have all been male.

Shoghi Effendi anticipated that the Universal House of Justice would be established as an all-male body, even though he passed away before he could see this implemented. He did not comment generally on the subject, and he does not seem to have devoted a great deal of time to the issue. But in answer to questions from individual Baha’is, some letters were written on the Guardian’s behalf by his secretaries which comment on the composition of the yet-to-be-formed House of Justice. For example, his secretary writes:

As regards your question concerning the membership of the Universal House of Justice, there is a Tablet from ‘Abdu’l-Baha in which He definitely states that the membership of the Universal House of Justice is confined to men, and that the wisdom of it will be fully revealed and appreciated in the future. In the local, as well as national Houses of Justice, however, women have the full right of membership. It is, however, only to the International House that they cannot be elected. [56]

And in another letter:

As regards the membership of the International House of Justice, ‘Abdu’l-Baha states in a Tablet that it is confined to men, and that the wisdom of it will be revealed as manifest as the sun in the future. [57]

Again:

Regarding your question, the Master said the wisdom of having no women on the International House of Justice, would become manifest in the future. We have no indication other than this… [58]

Again:

People must just accept the fact that women are not eligible to the International House of Justice. As the Master says the wisdom of this will be known in the future, we can only accept, believing it is right… [59]

The remarkable similarity of these letters to individual believers should be noted. In each case, the Guardian directed his secretary to refer to the Tablet of ‘Abdu’l-Baha to Corinne True which was written in reply to her petition that women be elected to the Chicago House of Justice. This Tablet explains that the reason for the exclusion of women will become manifest in the future.

Subsequent events demonstrated that ‘Abdu’l-Baha had intended that this exclusion be only temporary – an exclusion that would be followed by the full participation of women on this body.

The exclusion of women from the Universal House of Justice today is observed by the Baha’i community primarily in obedience to these letters of the Guardian. Most Baha’is assume that this exclusion was intended to be a permanent one. However, since this instruction of the Guardian is tied so closely to the meaning of the one Tablet of ‘Abdu’l-Baha which promises that the wisdom of the exclusion of women will become manifest in the future, and since it is known that the meaning of the Tablet was that women should be excluded only temporarily from the Chicago House, the assumption that women will be permanently excluded from the current Universal House of Justice may be a faulty one. A temporary exclusion may be intended.

The answer to this question, as with all other questions in the Baha’i community, will have to be worked out over time. The elements of dialogue, struggle, persistence and anguish which are so evident in the history of the gradual participation of women on local Baha’i administrative bodies will, no doubt, all attend the working out of that answer in the future. These elements are all present today.

A Tablet of Assurance

‘Abdu’l-Baha repeatedly assured Baha’i women in His writings that the women of the future would achieve full and complete equality with men. In one of these Tablets He refers to the composition of the House of Justice. The Tablet is dated August 28, 1913, and it appears to have been written to a Baha’i woman in the East. In it, ‘Abdu’l-Baha repeats His promise:

In this Revelation of Baha’u’llah, the women go neck and neck with the men. In no movement will they be left behind. Their rights with men are equal in degree. They will enter all the administrative branches of politics. They will attain in all such a degree as will be considered the very highest station of the world of humanity and will take part in all affairs.

Rest ye assured. Do ye not look upon the present conditions; in the not far distant future the world of women will become all-refulgent and all-glorious, For his Holiness Baha’u’llah hath willed it so! At the time of the elections the right to vote is the inalienable right of women, and the entrance of women into all human departments is an irrefutable and incontravertible question. No soul can retard or prevent it…

As regards the constitution of the House of Justice, Baha’u’llah addresses the men. He says: “O ye men of the House of Justice!” But when its members are to be elected, the right which belongs to women, so far as their voting and their voice is concerned, is indisputable. When the women attain to the ultimate degree of progress, then, according to the exigency of the time and place and their great capacity, they shall obtain extraordinary privileges. Be ye confident on these accounts. His Holiness Baha’u’llah has greatly strengthened the cause of women, and the rights and privileges of women is one of the greatest principles of ‘Abdu’l-Baha. Rest ye assured! [60] (Final emphasis added.)

Notes

1. Nabil-i A’zam, The Dawn-Breakers, Wilmette, Ill.: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1932, pp 80-81, 270-71.

2. See, for example, Ruhiyyih Rabbani, The Priceless Pearl, London: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1969, pp 39-42 and 57-58; Baha’i Administration, Wilmette, Ill.: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1928, pp 25-26.

3. The Universal House of Justice, A Synopsis and Codification of the Kitab-i-Aqdas, the Most Holy Book of Baha’u’llah, Haifa: Baha’i World Centre, 1973, p 5.

4. Ibid., pp 3-7.

5. ‘Abdu’l-Baha, The Promulgation of Universal Peace, Wilmette, Ill.: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1922-25 (1982), pp 136-37.

6. Ibid., pp 136-37.

7. ‘Abdu’l-Baha, Paris Talks, London: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1912, p 161.

8. Promulgation, p 174.

9. Ibid., p 375.

10. Synopsis, p 13.

11. Ibid., p 16.

12. Ibid., p 57.

13. Ibid., pp 5-6.

14. All information in this section concerning the first House of Justice of Tehran is based on Ruhu’llah Mihrabkhani, Mahafil-i shur dar ‘ahd-i Jamal-i Aqdas-i Abha, (Assemblies of consultation at the time of Baha’u’llah) in Payam-i Baha’i, nos. 28 and 29, pp 9-11 and pp 8-9 respectively.

15. Minutes of the North Hudson, N.J., Board of Counsel, National Baha’i Archives, Wilmette, Ill.

16. Chase to Blake, 21/3/00, Chase Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

17. Regulations relating to the Chicago Board of Council (Abdel Karim Effendi), Albert Windust Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

18. Kenosha Evening News, 29/6//00, p 1.

19. House of Justice in Chicago to House of Justice in New York 23/5/01, House of Spirituality Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

20. Fannie Lesch, “Dr. C. I. Thatcher, Chicago, Illinois”, (an obituary), Albert Windust Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

21. Minutes of the House of Justice (Chicago), 26/1/02 and 28/6/01. House of Spirituality Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

22. Marzieh Gail and Fadil-i Mazandarani (trans.), typescript translation of the Kitab-i Aqdas.

23. Ibid.

24. Quoted in Ahmad Yazdani, Mabadiy-i Ruhani, Tehran: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 104 Badi’, p 109.

25. Ibid

26. Women: Extracts from the Writings of Baha’u’llah, ‘Abdu’l-Baha, Shoghi Effendi, and the Universal House of Justice, comp. by The Research Department of the Universal House of Justice, Thornhill, Ont.: Baha’i Canada Publications, 1986, #7, p 3.

27. Quoted in Ahmad Yazdani, Maqam va Huquq-i Zan dar Diyanat-i Baha’i, vol. 1, Tehran: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 107 Badi’.

28. Minutes of the House of Spirituality, 24/5/01, House of Spirituality Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

29. Ibid., 20/5/01.

30. Synopsis, p 13.

31. Tablets of Abdul-Baha Abbas, Chicago: Baha’i Publishing Society, 1909, vol 1, p 3.

32. Shoghi Effendi, World Order of Baha’u’llah, Wilmette, Ill.: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1938, p 6.

33. Minutes of 10/5/02, House of Spirituality Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

34. Extract from the Tablet of the Master, ‘Abdu’l-Baha, to Mirza AssadUllah, received in Chicago on the 3rd of May, 1902. House of Spirituality Papers. National Baha’i Archives.

35. Tablets of Abdul Baha Abbas, p 6.

36. The translation reads “We named the assemblies of teaching in Chicago the Spiritual Assemblies; you should organize spiritual assemblies in every place”; ( extract from the Tablet from the Master, se note 35 above).

37. Minutes, 29/7/05, House of Spirituality Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

38. See various published Tablets and public talks of ‘Abdu’l-Baha, including: Kitab-i baday ‘u’l-athar, Bombay, 1921, vol.1, pp 65, 119, 120, 251; and

39. True to ‘Abdu’l-Baha, 25/2/02, Document 11137, International Baha’i Archives, Haifa, Israel.

40. Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Baha, Haifa: Baha’i World Centre, 1978, pp 79-80.

41. ‘Abdu’l-Baha to Corinne True, 24/7/09, microfilm, National Baha’i Archives. [JustaBahai addition:] The original translation by Ameen Fareed was made on July

29, 1909. There is a later translation of this tablet in The Baha’i Faith in America, Volume

Two, by Rob Stockman, page 323 made by the Baha’i World Centre for the book.

42. Chase to Remey, 19/1/10, Chase Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

43. Minutes, 31/8/09 and 7/9/09, House of Spirituality Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

44. Chase to Scheffler, 10/5/10, Chase papers, National Baha’i Archives.

45. Bahai Assembly of Kenosha to House of Spirituality, 4/7/10, House of Spirituality Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

46. House of Spirituality (Albert R. Windust, LIbrarian) to Board of Consultation, Kenosha, Wis., 23/7/10, House of Spirituality Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

47. Ibid.

48. Ibid.

49. Ibid.

50. Ibid.

51. Ibid.

52. Ibid. Kenosha Assembly to Albert Windust, 16/5/11, House of Spirituality Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

53. Ibid. ‘Abdu’l-Baha to the members of the Spiritual Assembly and Mr. Bernard M. Jacobsen, Kenosha, Wis., 4/5/11, House of Spirituality Papers, National Baha’i Archives.

54. Ibid. Star of the West, vol. 3, no. 10 (August 20, 1912) p 16. See also, ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s instructions to Howard MacNutt, August 6, 1912, microfilm collection, National Baha’i Archives.

55. Ibid. Women, #11, pp 6-7.

56. Letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, dated July 28, 1936, Baha’i News, No. 105 (February 1937) p 2.

57. Letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, dated December 14, 1940, quoted in Dawn of a New Day (New Delhi: Baha’i Publishing Trust, n.d.) p 86.

58. Letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, dated September 17, 1952, Baha’i News, No 267 (May 1953) p 10.

59. Letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, dated July 15, 1947, quoted in “Extracts on Membership of the Universal House of Justice” (an unpublished compilation of the Universal House of Justice).

60. Quoted in Paris Talks (London: Baha’i Publishing Trust, 1912) pp 182-83.

Editor’s Note: This paper was written in Los Angeles in 1988; many of the authors were young academics and intellectuals associated with dialogue Magazine. It was presented at an Association for Baha’i Studies conference in New Zealand the same year and was immediately suppressed by the Baha’i authorities, and its authors were forbidden to circulate it in any way.

Mirrored (with the addition on footnote 41) from http://www.h-net.org/~bahai/docs/vol3/wmnuhj.htm

This is the 2007 letter:

THE UNIVERSAL HOUSE OF JUSTICE DEPARTMENT OF THE SECRETARIAT

18 October 2007

Transmitted by email:

Mr. Romane Takkenberg

Australia

Dear Bahá’í Friend,

Your email message of 23 September 2007 has been received by the Universal House of Justice, which has asked us to respond as follows.

The document to which you refer, prepared by Mr. Anthony A. Lee and others, was circulated informally in the United States in the latter part of the 1980s and attracted some attention from those who studied it because of its statements about the possible future participation of women in the membership of the House of Justice.

TIt was then presented at a Bahá’í Studies conference in New Zealand, at which time it was brought to the attention of the House of Justice.

On 31 May 1988, the House of Justice wrote to the National Spiritual Assembly of New Zealand clarifying the issues raised in that paper. A copy of this letter is enclosed for your information.

The House of Justice is not aware of any attempt to restrict the circulation of the paper. However, it might reasonably be expected that it would not be accepted for publication in a reputable Bahá’í journal or as part of a compilation of papers in view of the clarification provided in the aforementioned letter of 31 May.

With loving Bahá’í greetings,

Department of the Secretariat

—

Some have argued that because Abdul-Baha changed the name (intended to be a temporary measure) in 1902 from House of Justice to a term without the word Justice in it, that this means that one day when the name Baha’u’llah gave them, House of Justice, is returned, then women will no longer be able to serve on them. However in 1912 when Abdul-Baha allowed women to be elected to the local House of Justice this meant in affect that he was interpreting Baha’ullah’s reference to ‘rijal’ as applying to women as well.

So where did the idea come from that women could not serve on the UHJ? The only source I can find for this are in the 4 letters written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi (1936, 1940, 1947, 1952) referred to in the paper above and all these letters seem to refer to Abdul-Baha’s 1902 Tablet because of their wording. My guess is, that the secretary was unaware that the context for Abdul-Baha’s 1902, 1909, and 1911 tablets were the all male membership of Local Spiritual Assemblies. The 1909 reference to ‘Universal’ seems to me to distnguish the administrative committee from the teaching and other committees women were members of referred to in the second part of the same tablet. The 1910 tablet addressed to the Bahais of Cincinnati encourages them to elect both men and women to a committee called the “Spiritual Assembly” where the context shows that this was not the ‘general local Assembly’, while a 1911 tablet informs the Bahais of Kenosha not to disband their all male “Board of Consultation”. Labels for the various local committees were fluid (explaining why the 1910 Cincinnati “Spiritual Assembly” was not the same as the ‘general’ or ‘universal’ administrative body) and that explains to me why Abdul-Baha used term ‘Universal’ to distinguish the various local committees from the main local administrative committee (known today as the Local Spiritual Assembly) which until 1912 could only have male members on them.

I have no idea if the UHj might ever decide that women will be allowed to be members but it seems as clear as the noon day sun to me that in 1912 Abdul-Baha either changed his interpretation of the word ‘rijal’ or saw that this was the time for implementing gender equality within the Bahai administration when he asked to have the Chicago Assembly disband its all male membership and then elect from the women and men in the community. And if Shoghi Effendi did not have the authority to dictate the membership of the UHJ, then surely any letters written on his behalf would have a lesser authority to do so:

“… the Guardian … He is debarred from laying down independently the constitution [of the Universal House of Justice] that must govern … and from exercising his influence in a manner that would encroach upon the liberty of those whose sacred right is to elect the body of his collaborators.” World Order of Baha’u’llah, p 150